We spoke with Sam Done, a UK farmer based in Lincolnshire, who’s farm has been successfully integrating sustainable practices into the malting barley operation for over a decade. Sam’s experience proves that a gradual, patient approach leads directly to improved soil health, greater climate resilience, stable yields, and consistent quality, all while maintaining farm profitability.

Q: Can you briefly describe your farm, the size of your barley operation, and what initially sparked your interest in transitioning to regenerative agriculture?

A: "We’re farming around 1,500 acres. Of that, there’s around 10% grassland, with some cattle on the farm, but the main focus is arable cropping. The start was actually more from the need to control black grass and then progressed to a soil health point of view. Cover cropping came in from a black grass perspective looking at can we help to suppress the problem weeds and reduce that issue."

Q: How long have you been doing regen ag for your farm? What year did you start?

A: "It probably would have been ten years ago when it became a more serious intention with straw being chopped and the shallowing out of cultivations. Fifteen years ago the farm management reviewed our able plan and thought we needed to change our processes and what we're doing in the within the rotation and widening it, but actually linking it to soil health as a main aim is probably around 10 years ago, I'd say."

Q: What specific barley varieties are you currently growing? And what are the key quality requirements mandated by the malting industry for those varieties?

A: "At the minute, our winter barley is Craft, but we trialled some Buccaneer last year which looks an interesting option going forward. Our spring barley variety is similarly being reviewed. We used Planet as our variety previously, and now we’re looking to go to Laureate. Our samples have both been pretty good from a specification point of view this year. I think the highest we’ve got is 1.79% Grain N (Nitrogen) on a little bit of poor-yielding winter stuff but overall we seem to have good quality grain from a potentially problematic dry spring period which is pleasing to see."

Q: What does regenerative agriculture look like on your farm? Can you please explain the chronological order of your key operations, from the previous harvest to the barley harvest, focusing on the core practices you've implemented?

A: Winter Barley: "Cultivation-wise, it's just minimal cultivations. We’ll effectively take the spring barley off, and then just a shallow cultivation—three inches, something like that—just to mix the chopped straw and take out any compaction from the combine tracks, with a controlled traffic farming system reducing the impact of grain carts. Whereas previously, we’d be working at 25 centimetres with a low-disturbance tine, but pretty heavily cultivated."

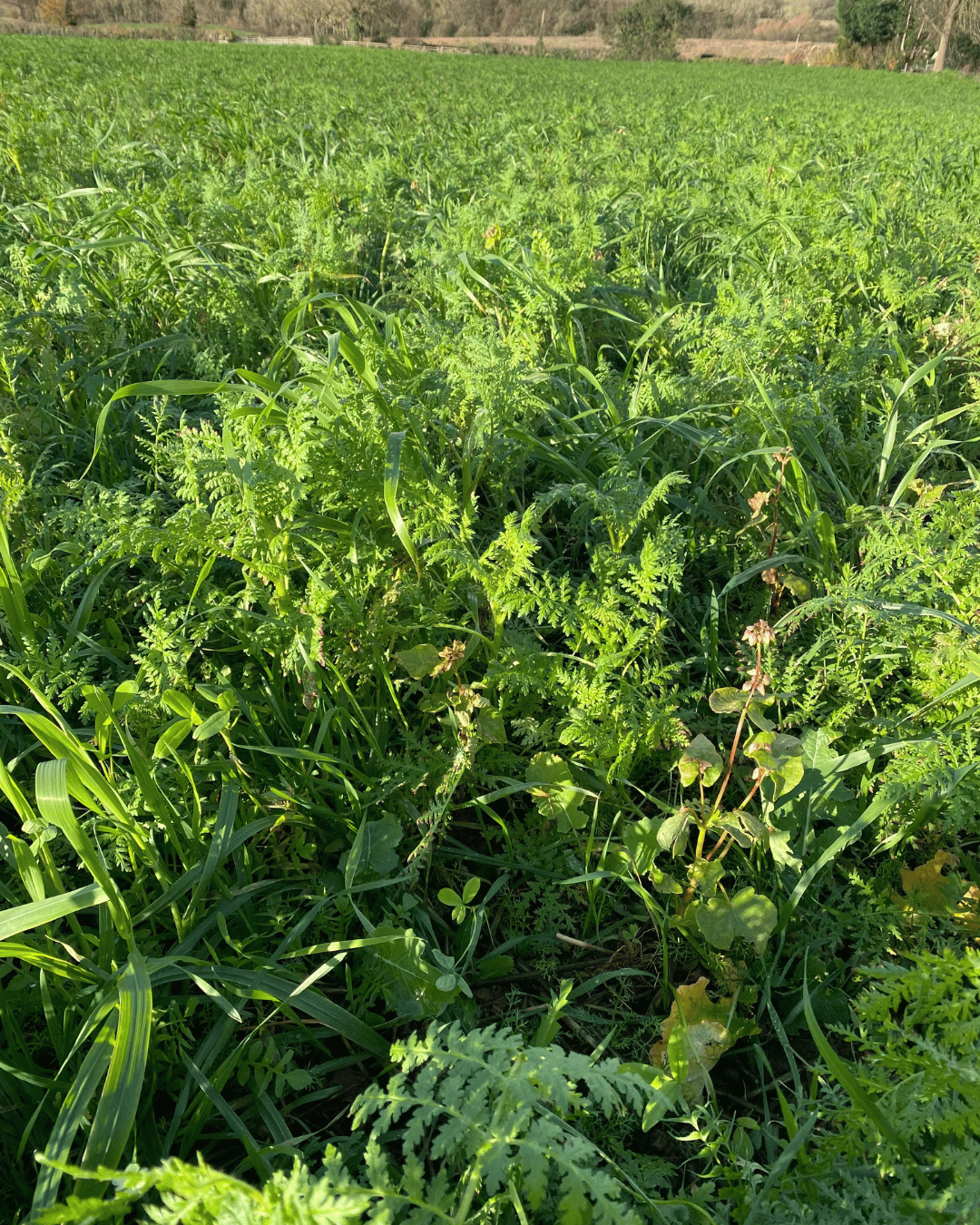

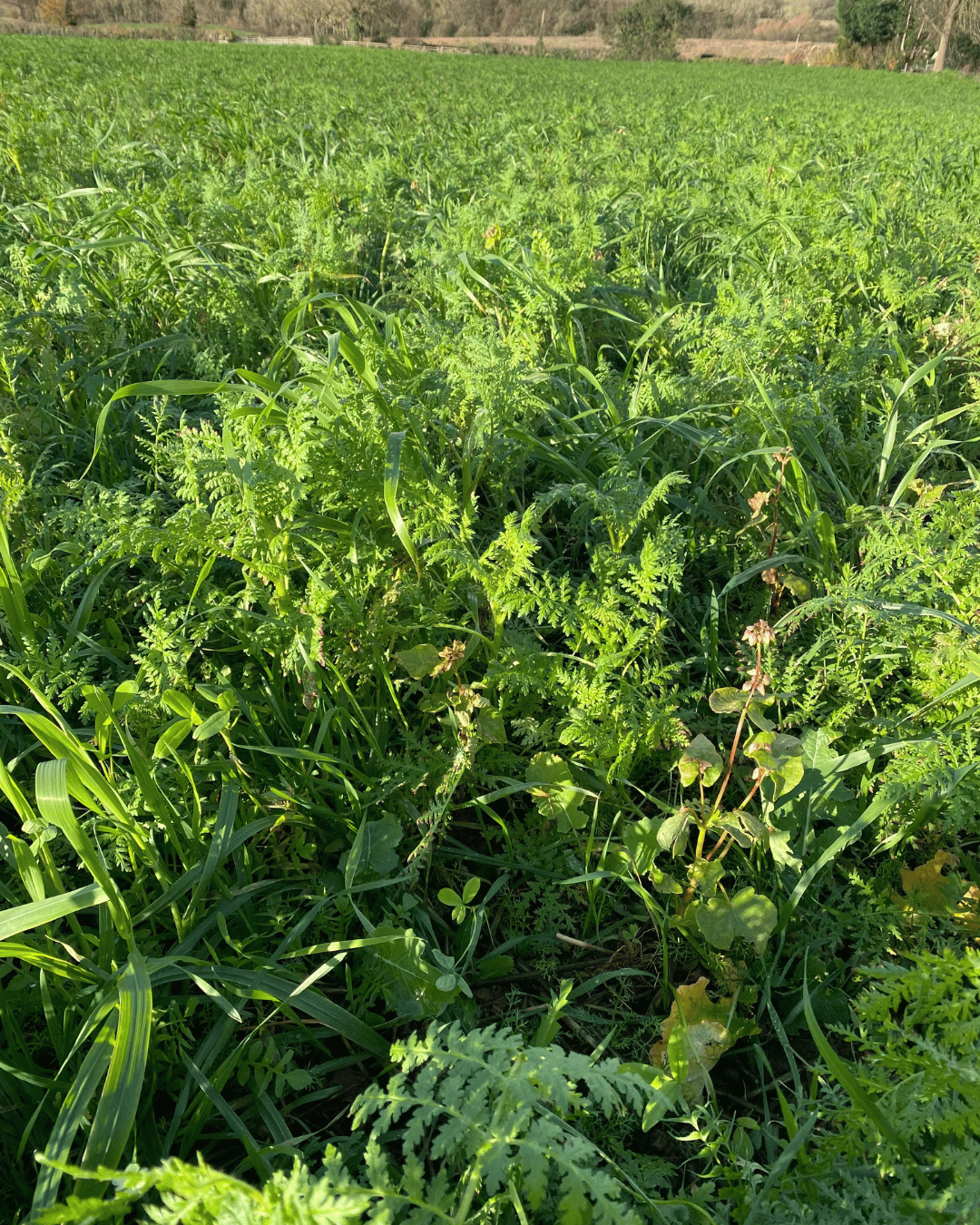

Spring Barley: "It’s quite a big change in that we would probably previously be on overwinter ploughing ten years or so ago but now, everything is cover cropped. We’re at six species this year in our cover crop mix. We see the root growth effectively as being a cultivator for us because they do such a good job of getting through compaction. Also the ground cover helps to protect the soils and limit capping from heavy rain, and in a wet time the roots seem to have created a good natural drainage system and structure to travel on, but then in a dry spring like this year, not moving the soil gives valuable moisture retention."

Q: What changes have you made to your overall rotation?

A: "If we us winter barley as a starting point, this is aimed to be malting standard. We follow that with oilseed rape, which will have a companion crop, followed by a winter wheat. That will then go into a cover crop, preparing the soil for spring beans. We will direct drill the beans into the cover crop, and then following on from beans, we will direct drill wheat into that if the conditions are suitable. That's the only time we will direct drill a winter crop with the others getting some shallow correctional cultivations. Then for a second time within the rotation, we follow winter wheat with the same cover crop mix, which then goes into spring barley, once again targeting malting premiums, and the barley then loops back around into the winter barley following that."

Q: Which types of cover crops did you introduce before or after barley, and what was your biggest learning curve regarding their management?

A: "We’re at six species now in our cover crop. So we have vetch, buckwheat and black oats, which are the three larger seeds that we put in there. We’ve also got berseem clover, phacelia, and linseed as well. Currently we mix the ratios ourselves but use a split tanks helping us to keep the larger and smaller seeds apart which reduces the separation of the seed types when drilling. You do very much have to bend to what nature is offering you in terms of drilling into the covers in spring and sometimes have got to be a bit more patient to allow the seed the best starting conditions to grow, but also we’ve found that making sure you can get the covers well destroyed is important."

Q: Have you reduced tillage intensity, and what challenges did that present for barley establishment and root development specifically?

A: "We’ve had four springs direct drilling into covers now. It can look like it’s a little bit slower than some of the other fields that have been cultivated initially. I think there’s a little bit more air there, and potentially it’s easier for the roots to start moving rather than a more solid structure. But generally, we see that the direct drilled spring stuff does catch up during May/June, the peak growing seasons, when potentially some of the roots in other plants are stopping at a plough pan or a compacted area. By having those root and better soil structures. That’s when we see our plant really developing and hopefully catching up, if not growing past the alternative, using the retain nutrients and moisture to the plants advantage."

Q: How have you adjusted your nitrogen fertilizer strategy to manage yield while maintaining the low protein content required for malting quality?

A: "We use granular fertilizer. The biggest thing that we’re trying to do from that point of view is get it on nice and early. We try to keep that nitrogen away from the grain development in malting barleys because we don't want it creating specification issues. The thing with organic manures that we find is, A, it’s hard to predict what’s actually in it—it’s not that consistent—but equally, when the plant will actually take it up. So we’re a little bit safer, really, and we are using granules at the minute from that point of view."

Q: What has been the evolution of your malting barley protein specification, yield, and overall quality over the last few years since transitioning to regenerative practices, and are you seeing more consistency compared to conventional years?

A: "We've not really seen an issues [with protein]. Nutrient-wise and fertiliser-wise, we’ve not changed too much yet. I wouldn’t say we’ve cut back, but we’ve definitely not seen any negative impacts in terms of specs and nitrogen levels in the grain and the main focus for us is to get the nitrogen rates and timings right.."

Q: Do you feel / see more resilience against climate extremes, and how does that improved resilience translate into more stable production for your buyers?

A: "I think throughout that rotation, we're seeing that there’s more resilience to poor years, whether that’s dry or wet. By having the soil structures in a better condition through cover cropping and reduced tillage, it’s helping our soils fight for themselves rather than us having to keep hitting the reset button with them. An average yield in a year that could have quite easily been very poor has to be seen as a success. Having better soil structures and resilience is probably the biggest thing that we've seen to benefit from with moving towards sustainable min-till processes."

Q: Can you share the evolution of your malting barley yields over the last few years since transitioning to regenerative practices?

A: "We’ve not seen any yield reductions, from what we’re doing. I think if you jumped into the process too quickly, you could, if your soils weren’t ready to do it. If you’re patient — it depends on your soil types and the mother nature — but three to five years of gradually reducing your tillage, and incorporating organic matter, you don’t have to take backwards steps. We don’t see it as a major issue trying to do what we’re doing, more of a gradual and patient progression to set up the foundations for the future."

Q: How has the adoption of regenerative practices impacted the revenue generated from your malting barley sales in recent years?

A: "We are seeing a good reduction in our costings because we’re not spending as much money on wearing parts, time and labour for doing the cultivations that we’re not having to do, really. Also trying to use environmental schemes for additional income with the cover cropping helps. It’s trying to do the little 1% gains here and there and get all the little achievements to add up together."

Q: To whom do you sell your malting barley? Do you sell to the same buyer every year, and if so, why? Do you use a multi-year contract?

A: "Molson Coors is who we sell ours to. So there's a grain merchant that approaches us. We effectively commit to three years. Generally, the prices and premiums they’re offering are better than the market premium—that’s how they get you committed to growing for them. We’re trying to aim to go for the high-quality crops. We try to think that if we can continuously grow a good product, they’re going to want to keep the same farmers for their benefit as much as ours."

Q: Have financial incentives been important in your decisions, and how have they impacted your overall farm economics?

A: "Part of that is diversification and other forms of income, and that’s for us where Soil Capital comes in. It’s basically supporting us to do what we’re doing, and it’s another form of income and string to our bow. From a barley point of view, Soil Capital is the direct link to that. Also trying to work with SFI options that may or may not be available is important."

Q: What practical, agronomic advice or data insights have you received from Soil Capital that made a significant difference to your barley crop or soil health?

A: "We’re looking at how that lines up with Soil Capital. Which practices that we should be doing, shouldn’t be doing, more so than others. We are very much making decisions based on what the crops and soil need to yield as our primary focus. We aren’t looking to change our practices to create potential income from Soil Capital, but currently what we’re doing lines up well with the Soil Capital incentives."

Q: What was the single biggest challenge you faced when you decided to implement the first few regenerative practices, and how did you overcome it?

A: "I think knowledge is a difficult part. You need to be trying to pick the brain of people that have been down that journey. And equally, equipment. I think a lot of people potentially look at it and think, 'Well, it’s going to be a massive expense for us' but I think there’s a natural progression that as you start heading towards sustainable agriculture and using different cultivations, when you’re replacing older equipment, it’s quite doable on a spaced out period of time and just updating machinery as part of balanced capital expenditure plan rather than 'We need to go and spend a fortune all in one go.'"

Q: If you could imagine the “ideal partnership” with a buyer in the beer industry, what would it look like in terms of commitment, support, and shared goals?

A: "It’d be nice to see companies really valuing that sustainability of a product, because I think at the end of the line, there are a lot of customers that will value the fact that you’re trying to have a sustainable product and looking at trying to protect animals, insects, and soil health. It’s trying to bridge that gap from farmers actually doing it on the farm and doing what they’re saying, and it benefiting the maltsters and end users as well."

Q: What would be the advice for a fellow farmer that is thinking of transitioning?

A: "I think you’ve got to try and convince yourself that it’s going to work. By looking and working with farmers that have potentially started the journey or companies that are further down the journey. We probably wouldn’t have jumped to these steps if we hadn’t seen it working already. Learn from their mistakes and successes and try to tailor it to your farm, rotation and soil type. Where in your rotation can you start reducing your tillage and potentially looking at cover cropping if there’s a natural start to that? Do half a field or leave two tramlines where you haven’t cultivated it. You’re not going to lose that much by having a go."

Q: Looking ahead, what is your vision for malting barley on your farm in 5–10 years, and what broader benefits do you hope to achieve?

A: "The malting barley side of it fits in really nicely to our overall aim of a wider rotation as well. It’s a nice spring crop in there allowing the benefits of cover cropping, but also the winter barleys early harvest helps spread out our demand during peak season. Looking at things like flower strips all the way around the fields, whether we’re going to have six metres around there for beneficiaries and biodiversity is an option. Hopefully, a progression for purchasers and customers to see what we are doing on the farm and trying to add value to that product, not just producing malting barley, but actually doing it to help nature and work with it."

.png)

We spoke with Sam Done, a UK farmer based in Lincolnshire, who’s farm has been successfully integrating sustainable practices into the malting barley operation for over a decade. Sam’s experience proves that a gradual, patient approach leads directly to improved soil health, greater climate resilience, stable yields, and consistent quality, all while maintaining farm profitability.

Q: Can you briefly describe your farm, the size of your barley operation, and what initially sparked your interest in transitioning to regenerative agriculture?

A: "We’re farming around 1,500 acres. Of that, there’s around 10% grassland, with some cattle on the farm, but the main focus is arable cropping. The start was actually more from the need to control black grass and then progressed to a soil health point of view. Cover cropping came in from a black grass perspective looking at can we help to suppress the problem weeds and reduce that issue."

Q: How long have you been doing regen ag for your farm? What year did you start?

A: "It probably would have been ten years ago when it became a more serious intention with straw being chopped and the shallowing out of cultivations. Fifteen years ago the farm management reviewed our able plan and thought we needed to change our processes and what we're doing in the within the rotation and widening it, but actually linking it to soil health as a main aim is probably around 10 years ago, I'd say."

Q: What specific barley varieties are you currently growing? And what are the key quality requirements mandated by the malting industry for those varieties?

A: "At the minute, our winter barley is Craft, but we trialled some Buccaneer last year which looks an interesting option going forward. Our spring barley variety is similarly being reviewed. We used Planet as our variety previously, and now we’re looking to go to Laureate. Our samples have both been pretty good from a specification point of view this year. I think the highest we’ve got is 1.79% Grain N (Nitrogen) on a little bit of poor-yielding winter stuff but overall we seem to have good quality grain from a potentially problematic dry spring period which is pleasing to see."

Q: What does regenerative agriculture look like on your farm? Can you please explain the chronological order of your key operations, from the previous harvest to the barley harvest, focusing on the core practices you've implemented?

A: Winter Barley: "Cultivation-wise, it's just minimal cultivations. We’ll effectively take the spring barley off, and then just a shallow cultivation—three inches, something like that—just to mix the chopped straw and take out any compaction from the combine tracks, with a controlled traffic farming system reducing the impact of grain carts. Whereas previously, we’d be working at 25 centimetres with a low-disturbance tine, but pretty heavily cultivated."

Spring Barley: "It’s quite a big change in that we would probably previously be on overwinter ploughing ten years or so ago but now, everything is cover cropped. We’re at six species this year in our cover crop mix. We see the root growth effectively as being a cultivator for us because they do such a good job of getting through compaction. Also the ground cover helps to protect the soils and limit capping from heavy rain, and in a wet time the roots seem to have created a good natural drainage system and structure to travel on, but then in a dry spring like this year, not moving the soil gives valuable moisture retention."

Q: What changes have you made to your overall rotation?

A: "If we us winter barley as a starting point, this is aimed to be malting standard. We follow that with oilseed rape, which will have a companion crop, followed by a winter wheat. That will then go into a cover crop, preparing the soil for spring beans. We will direct drill the beans into the cover crop, and then following on from beans, we will direct drill wheat into that if the conditions are suitable. That's the only time we will direct drill a winter crop with the others getting some shallow correctional cultivations. Then for a second time within the rotation, we follow winter wheat with the same cover crop mix, which then goes into spring barley, once again targeting malting premiums, and the barley then loops back around into the winter barley following that."

Q: Which types of cover crops did you introduce before or after barley, and what was your biggest learning curve regarding their management?

A: "We’re at six species now in our cover crop. So we have vetch, buckwheat and black oats, which are the three larger seeds that we put in there. We’ve also got berseem clover, phacelia, and linseed as well. Currently we mix the ratios ourselves but use a split tanks helping us to keep the larger and smaller seeds apart which reduces the separation of the seed types when drilling. You do very much have to bend to what nature is offering you in terms of drilling into the covers in spring and sometimes have got to be a bit more patient to allow the seed the best starting conditions to grow, but also we’ve found that making sure you can get the covers well destroyed is important."

Q: Have you reduced tillage intensity, and what challenges did that present for barley establishment and root development specifically?

A: "We’ve had four springs direct drilling into covers now. It can look like it’s a little bit slower than some of the other fields that have been cultivated initially. I think there’s a little bit more air there, and potentially it’s easier for the roots to start moving rather than a more solid structure. But generally, we see that the direct drilled spring stuff does catch up during May/June, the peak growing seasons, when potentially some of the roots in other plants are stopping at a plough pan or a compacted area. By having those root and better soil structures. That’s when we see our plant really developing and hopefully catching up, if not growing past the alternative, using the retain nutrients and moisture to the plants advantage."

Q: How have you adjusted your nitrogen fertilizer strategy to manage yield while maintaining the low protein content required for malting quality?

A: "We use granular fertilizer. The biggest thing that we’re trying to do from that point of view is get it on nice and early. We try to keep that nitrogen away from the grain development in malting barleys because we don't want it creating specification issues. The thing with organic manures that we find is, A, it’s hard to predict what’s actually in it—it’s not that consistent—but equally, when the plant will actually take it up. So we’re a little bit safer, really, and we are using granules at the minute from that point of view."

Q: What has been the evolution of your malting barley protein specification, yield, and overall quality over the last few years since transitioning to regenerative practices, and are you seeing more consistency compared to conventional years?

A: "We've not really seen an issues [with protein]. Nutrient-wise and fertiliser-wise, we’ve not changed too much yet. I wouldn’t say we’ve cut back, but we’ve definitely not seen any negative impacts in terms of specs and nitrogen levels in the grain and the main focus for us is to get the nitrogen rates and timings right.."

Q: Do you feel / see more resilience against climate extremes, and how does that improved resilience translate into more stable production for your buyers?

A: "I think throughout that rotation, we're seeing that there’s more resilience to poor years, whether that’s dry or wet. By having the soil structures in a better condition through cover cropping and reduced tillage, it’s helping our soils fight for themselves rather than us having to keep hitting the reset button with them. An average yield in a year that could have quite easily been very poor has to be seen as a success. Having better soil structures and resilience is probably the biggest thing that we've seen to benefit from with moving towards sustainable min-till processes."

Q: Can you share the evolution of your malting barley yields over the last few years since transitioning to regenerative practices?

A: "We’ve not seen any yield reductions, from what we’re doing. I think if you jumped into the process too quickly, you could, if your soils weren’t ready to do it. If you’re patient — it depends on your soil types and the mother nature — but three to five years of gradually reducing your tillage, and incorporating organic matter, you don’t have to take backwards steps. We don’t see it as a major issue trying to do what we’re doing, more of a gradual and patient progression to set up the foundations for the future."

Q: How has the adoption of regenerative practices impacted the revenue generated from your malting barley sales in recent years?

A: "We are seeing a good reduction in our costings because we’re not spending as much money on wearing parts, time and labour for doing the cultivations that we’re not having to do, really. Also trying to use environmental schemes for additional income with the cover cropping helps. It’s trying to do the little 1% gains here and there and get all the little achievements to add up together."

Q: To whom do you sell your malting barley? Do you sell to the same buyer every year, and if so, why? Do you use a multi-year contract?

A: "Molson Coors is who we sell ours to. So there's a grain merchant that approaches us. We effectively commit to three years. Generally, the prices and premiums they’re offering are better than the market premium—that’s how they get you committed to growing for them. We’re trying to aim to go for the high-quality crops. We try to think that if we can continuously grow a good product, they’re going to want to keep the same farmers for their benefit as much as ours."

Q: Have financial incentives been important in your decisions, and how have they impacted your overall farm economics?

A: "Part of that is diversification and other forms of income, and that’s for us where Soil Capital comes in. It’s basically supporting us to do what we’re doing, and it’s another form of income and string to our bow. From a barley point of view, Soil Capital is the direct link to that. Also trying to work with SFI options that may or may not be available is important."

Q: What practical, agronomic advice or data insights have you received from Soil Capital that made a significant difference to your barley crop or soil health?

A: "We’re looking at how that lines up with Soil Capital. Which practices that we should be doing, shouldn’t be doing, more so than others. We are very much making decisions based on what the crops and soil need to yield as our primary focus. We aren’t looking to change our practices to create potential income from Soil Capital, but currently what we’re doing lines up well with the Soil Capital incentives."

Q: What was the single biggest challenge you faced when you decided to implement the first few regenerative practices, and how did you overcome it?

A: "I think knowledge is a difficult part. You need to be trying to pick the brain of people that have been down that journey. And equally, equipment. I think a lot of people potentially look at it and think, 'Well, it’s going to be a massive expense for us' but I think there’s a natural progression that as you start heading towards sustainable agriculture and using different cultivations, when you’re replacing older equipment, it’s quite doable on a spaced out period of time and just updating machinery as part of balanced capital expenditure plan rather than 'We need to go and spend a fortune all in one go.'"

Q: If you could imagine the “ideal partnership” with a buyer in the beer industry, what would it look like in terms of commitment, support, and shared goals?

A: "It’d be nice to see companies really valuing that sustainability of a product, because I think at the end of the line, there are a lot of customers that will value the fact that you’re trying to have a sustainable product and looking at trying to protect animals, insects, and soil health. It’s trying to bridge that gap from farmers actually doing it on the farm and doing what they’re saying, and it benefiting the maltsters and end users as well."

Q: What would be the advice for a fellow farmer that is thinking of transitioning?

A: "I think you’ve got to try and convince yourself that it’s going to work. By looking and working with farmers that have potentially started the journey or companies that are further down the journey. We probably wouldn’t have jumped to these steps if we hadn’t seen it working already. Learn from their mistakes and successes and try to tailor it to your farm, rotation and soil type. Where in your rotation can you start reducing your tillage and potentially looking at cover cropping if there’s a natural start to that? Do half a field or leave two tramlines where you haven’t cultivated it. You’re not going to lose that much by having a go."

Q: Looking ahead, what is your vision for malting barley on your farm in 5–10 years, and what broader benefits do you hope to achieve?

A: "The malting barley side of it fits in really nicely to our overall aim of a wider rotation as well. It’s a nice spring crop in there allowing the benefits of cover cropping, but also the winter barleys early harvest helps spread out our demand during peak season. Looking at things like flower strips all the way around the fields, whether we’re going to have six metres around there for beneficiaries and biodiversity is an option. Hopefully, a progression for purchasers and customers to see what we are doing on the farm and trying to add value to that product, not just producing malting barley, but actually doing it to help nature and work with it."

.png)